Helping countries transition from donor aid for health: recent experience at the Global Fund

Dr. Robert Hecht and Rachel Wilkinson of Pharos Global Health Advisers comment on the role of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria in building sustainable funding structures for health system strengthening in middle income countries.

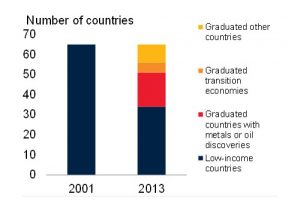

The global landscape of donor aid for health is rapidly changing: donor funding has plateaued, and many middle income countries (MICs), home to most of the world’s poor, have transitioned or are rapidly transitioning towards self-sufficiency and an end to financial backing from outside donor organizations – a process that has also been called “graduation” from donor assistance (see graph).

Transition from Low to Middle Income Countries, 2001-13

In this dynamic environment, donors need to shift their priorities from providing funding for disease-specific programs to offering technical insights and advice on ways the MICs can strengthen their health systems and sustain financing as the donors withdraw.

The Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis and Malaria’s “Special Initiative on Value for Money and Financial Sustainability” provides an example of how donor agencies can support transitioning countries. Using less than $10 million – a tiny fraction of its annual $3 billion budget — the Global Fund has seeded a wide range of catalytic activities. These include:

- Development and testing of new tools for assessing country readiness to transition away from donor aid.

- Building stronger collaborations between health and finance ministry officials.

- Experimenting with innovative sources of domestic funding to keep critical services, such as treating patients with multi-drug resistant tuberculosis and testing children with fever for malaria, solvent.

As we have argued elsewhere, the Global Fund should maintain this catalytic support. Other major global health programs bankrolled by the United States President’s Emergency Program for AIDS Relief (PEPFAR), the World Bank, and the UK’s Department for International Development (DFiD) also need to move in the same direction.

The Changing Landscape

After rising throughout the “golden era” of international aid for health between 2000 and 2010, donor funding has stabilized at just over $35 billion annually while needs continue to grow. At the same time, many countries (such as Brazil and Argentina in Latin America, Georgia and Ukraine in East Europe, Thailand and Indonesia in East Asia) have moved from lower-middle income to middle income status. As a result, these countries are transitioning out of eligibility for aid from large multilaterals such as the Global Alliance for Vaccines and Immunization (Gavi) and the Global Fund.

In an environment where donor aid is declining overall and shifting away from MICs to the poorest low-income countries (such as Malawi, Mozambique, and Haiti), donor agencies and affected MIC governments must prioritize transition readiness and the adopt smart financing policies. These steps are necessary to ensure the long-term survival of key health programs which serve hundreds of millions of people and are averting millions of illnesses and deaths.

The Global Fund currently supports 120 countries, twenty-four of which are MIC nations expected to transition away from Global Fund financing by 2025 for at least one of the three killer diseases.

The Global Fund’s Special Initiative

In light of these looming changes, the Fund launched the Special Initiative on Value for Money and Financial Sustainability in 2014. The initiative is designed to help countries diagnose and address the largest risks associated with their transitions, monitor and expand their own home-grown spending and explore innovative approaches that could generate additional resources to fight the three diseases.

Our recent review of the initiative found that it is having an important positive impact on country readiness to transition. Notable successes include:

- The Curatio Foundation, based in Tblisi Georgia, developed a transition preparedness assessment (TPA) tool, enabling countries in Eastern Europe and Central Asia (EECA) to map financing gaps and assess risks. The tool has been used in Belarus and Ukraine. Curatio is also training health officials in Uzbekistan, Armenia, Kyrgyzstan, and Moldova, and a modified version of the tool is spreading to Latin America and North Africa.

- Senior budget officials networks, sponsored by the OECD, are bringing together top representatives of ministries of health and finance in Asia, Latin America, and EECA to address health financing issues. A survey of budgeting practices found widespread weaknesses in MICs, such as failure to purchase inexpensive generic drugs listed in national formularies, that need to be rectified.

- A team of researchers from the Harvard School of Public Health examined AIDS trust funds as a potential new financing mechanism. Based on evidence from Zimbabwe, Tanzania, Uganda, and Kenya, they found that such trust funds would be vulnerable to economic shocks and might cause fiscal distortions. As a result, the African countries are now approaching these trust funds with greater caution and considering ways to pay for AIDS services from other public and private sources.

We also identified shortcomings in the Global Fund’s technical assistance that need to be addressed. For example:

- The SBO-health network for Africa was not able to demonstrate impact on country level decisions on resource mobilization for health. To do so, the network may need to enlist help from others such as the African Development Bank, World Bank, and WHO.

- The Global Fund’s support to South Africa to launch a development impact bond (DIB) to prevent HIV infections among female commercial sex workers has stalled, because of difficulties in finding a government sponsor for the project and wavering support among national stakeholders. While DIBs hold the potential to unlock new financing from private investors and test new ways to deliver AIDS services to stigmatized groups like sex workers and people who inject drugs, the design of DIBs may need to be simplified to get them off the ground.

Building on Success

This recent experience of the Global Fund under the Special Initiative shows how carefully crafted technical support to MICs can help put them on a more efficient and sustainable path as they end dependency on donor aid. It also illustrates how small amounts of donor aid can be leveraged to generate enormous global knowledge, that can safeguard health gains for hundreds of millions of people in MICs.

Featured Image: Nursing students in training. Yogyakarta, Indonesia. Project HPEQ. Photo: Nugroho Nurdikiawan Sunjoyo / World Bank. Photo ID: NNS-ID006 World Bank. Photo reproduced under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0 license.

About the Authors

Dr. Robert Hecht is the President of Pharos Global Health Advisors. He has more than 30 years of experience in global health, nutrition and development, in senior management positions with the World Bank, UNAIDS, the International AIDS Vaccine Initiative and Results for Development. Rob is a widely-recognized thought leader and policy analyst with a strong track record of advice to top decision makers and dozens of publications related to immunization, HIV, health financing, health sector reform, and nutrition. He holds a PhD from Cambridge University and a BA from Yale.

Rachel Wilkinson is an associate program officer at Pharos Global Health. At Pharos, she focuses on sexual and reproductive health and adolescent health issues. She previously worked as a research assistant at the BRAC University James P. Grant School of Public Health in Dhaka, Bangladesh focused on the health implications of early and child marriage. She holds a BA from Yale University where she majored in political science with a health policy concentration.

Dr. Hecht and Ms. Wilkinson highlight a number of important issues. One of the “million dollar questions” is, “how do we motivate governments to tackle the challenges facing stigmatized key populations, like sex workers or men who have sex with men, when they do not wish to do so?” This highlights a global failing in policy advocacy with policymakers and it was terrific to read of Pharos’ efforts in this regard.

Brazil, Georgia, Ukraine, Thailand are high income countries. Argentina is a very high income country. See Human Development Report by the World Bank.

Great blog thank you. It is also good you cross reference to Gavi’s work and recent evidence from the WHO UHC group that external donor support does displace domestic financing for health in many situations. I wonder whether the next step would be looking at the incentives for Goverments to keep items ‘ on budget’ transparently and for donors to work more coherently under the emerging UHC2030 framework?