Talking about Drug Prices & Access to Medicines Pt 1: By Els Torreele, Open Society Foundations

Welcome to a PLOS BLOGS six-part series, Talking about Drug Prices & Access to Medicines. To borrow a phrase from one of our bloggers, “Rage and public outcries are not a rational way to manage high drug prices.” We agree, while also acknowledging that the recent public and media uproar over the 5000% price hike and subsequent “roll back” of a 40 year old medicine by Turing Pharmaceuticals may have opened a useful window on larger issues, including misaligned incentives around drug R&D efforts and the related unavailability of necessary medicines to people around the world.

Each post presents a different point of view on these issues, and we encourage you to read all six parts — with titles and authors listed at the bottom of this post. For the series, PLOS BLOGS Network benefited from the involvement of PLOS Medicine Chief Editor, Larry Peiperl. — Victoria Costello, PLOS BLOGS Network

Only a radical overhaul can reclaim medicines for the public interest

By Els Torreele

Director, Access to Medicines

Public Health Program, Open Society Foundations

Medicines price gauging caught the public’s attention last month when Turing Pharmaceuticals raised, overnight, the price of a 60-year old anti-infective drug from $13.50 to $750 per pill. Although the ploy garnered unique public backlash, arbitrary price setting and extreme profiteering has become the industry rule rather than the exception. Valeant Pharmaceuticals has been hiking prices of existing drugs for years and new medicines prices have never been higher: Gilead’s $1000 per pill hepatitis C drug Sovaldi and Sanofi’s $11,000 per month colon cancer drug Zaltrap both provoked outcry from patients and doctors alike. Financial markets however rejoiced.

Insufficient price controls, overreaching patent laws, and other permissive legal and policy frameworks allow drug companies to price their medicines as high as they can get away with—relentlessly pushing the boundaries of both decency, and what patients, public health systems and private insurers can afford. Novartis’ cancer drug Gleevec was launched in 2001 at $30,000 per year, but now runs more than $100,000, though it costs a mere $159 to manufacture. Similarly, Pfizer arbitrarily raised the prices of 133 older drugs this past year.

The unaffordability of medicines is no longer just a problem for poor people in developing countries—it is a global public health emergency. Excessive prices stand between North American and European patients and life-saving treatments. Strained health budgets lead states and insurers to delay or ration expensive medicines and increase out-of-pocket expenses. To get the drugs they need, patients must suffer serious “financial toxicity,” as cancer doctor Leonard Saltz poignantly puts it, or forego treatment altogether.

While shocking for wealthy welfare states, the lack of affordable access to medicines has long been a reality for people living in low- and middle-income countries. This was most evident in the late 1990s, when new medicines turned the fatal HIV infection into a chronic and manageable disease. Priced at $10,000 per year, these treatments were unaffordable for millions of people dying in Africa, Asia and Latin-America. Inspiringly, health activists across the world publicly twisted the arms of drug companies and policymakers in the early 2000’s, bringing down prices to less than $100 per year and enabling treatment for over 15 million people today.

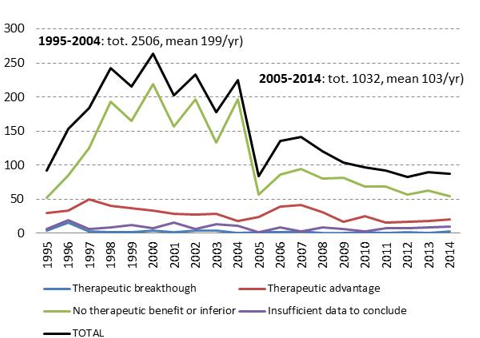

But despite this impressive “patient rights before patent rights” victory, the way the world finances and rewards medical innovation is more problematic than ever. The oft-cited but unfounded justification for high prices is the need to recoup expensive and risky R&D, and to fund future innovation. Though drug companies won’t disclose development costs, we know they rely heavily on publicly funded research. We also know that companies spend more on marketing drugs than on R&D, and more recently also on buying-back their own stocks to artificially keep share prices high. But more critically, despite growing R&D spending, the industry is largely investing in me-too “innovation”, delivering drugs that have no added therapeutic value over existing treatments, over 70% of all newly marketed drug —and there are no signs that true medical innovation is increasing (Fig. 1).

Where there is innovation, R&D priorities align with profits rather than public health needs. In 2014, 41% of new drugs approved by the FDA targeted rare diseases, for which high prices and generous profit margins are guaranteed. This focus on profitability sidelines medical innovation to address the health needs of millions of people globally, such as emerging drug-resistant infections (including the superbugs that haunt even the best equipped Western hospitals) and many common diseases like tuberculosis, Chagas disease, or dengue fever. And also the recent Ebola outbreak, killing over 11,000 people for lack of a vaccine or treatment despite Ebola being a known health threat for many years, is a stark wake-up call. Our medical innovation paradigm is ill-suited to respond to priority health needs.

Out-of-control drug pricing, R&D that focuses on the most profitable niche market segments, wasteful me-too drugs that rely on massive marketing to boost revenues, and critical unmet health needs—these are not just symptoms of an ailing R&D system but the expected result of a financialized business model designed to maximize profit and exhilarate the markets. Despite delivering only few therapeutic breakthroughs, the pharmaceutical industry generates higher profit margins than any other.

While public and private sectors bear collective responsibility for the current imbroglio, a radical policy overhaul is needed to reclaim a people- and health needs-driven medical innovation system. The successful fight for access to AIDS medicines has shown just how powerful public action can be to drive change. The Open Society Foundations is supporting diverse networks of experts and activists to advance new ideas and solutions to transform medical innovation in the public interest. As Einstein famously said, “we cannot solve our problems with the same thinking we used when we created them.”

The world deserves effective, affordable treatments that are public goods.

Els Torreele is the director of the Public Health Program’s Access and Accountability Division at the Open society Foundations (OSF). Torreele graduated as a bioengineer and obtained a PhD in applied biological sciences from the Free University Brussels. As a R&D coordinator at the Flanders Interuniversity Institute for Biotechnology, she worked on policy issues related to biomedical research agenda-setting, patenting of (public) research findings, and the commercialization of biotechnology research. Torreele joined the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Access to Essential Medicines Campaign in its pioneering years as chair of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Working Group, a think tank to come up with new ideas to foster needs-driven R&D of treatments for diseases that primarily affect developing countries. A key outcome of this group was the creation in 2003 of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), a nonprofit drug development organization which she joined as a founding team member. She joined OSF in 2009 to lead their Access to Medicines work, focusing on advancing health and human rights with a focus on transparency and accountability and supporting civil society voices in national, regional and global policy making that shapes access to medicines and biomedical innovation. On Twitter @ElsTorreele

Els Torreele is the director of the Public Health Program’s Access and Accountability Division at the Open society Foundations (OSF). Torreele graduated as a bioengineer and obtained a PhD in applied biological sciences from the Free University Brussels. As a R&D coordinator at the Flanders Interuniversity Institute for Biotechnology, she worked on policy issues related to biomedical research agenda-setting, patenting of (public) research findings, and the commercialization of biotechnology research. Torreele joined the Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF) Access to Essential Medicines Campaign in its pioneering years as chair of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases Working Group, a think tank to come up with new ideas to foster needs-driven R&D of treatments for diseases that primarily affect developing countries. A key outcome of this group was the creation in 2003 of the Drugs for Neglected Diseases initiative (DNDi), a nonprofit drug development organization which she joined as a founding team member. She joined OSF in 2009 to lead their Access to Medicines work, focusing on advancing health and human rights with a focus on transparency and accountability and supporting civil society voices in national, regional and global policy making that shapes access to medicines and biomedical innovation. On Twitter @ElsTorreele

The opinions expressed in this blog post reflect solely the views of its author, and not necessarily those of PLOS.

Pt 2. This Blogs Post is Going to Cost You by Jessica Wapner

Pt 3. If you play with scorpions, don’t be surprised when you get stung By Atif Kukaswadia

Pt 4. Drug pricing is out of control, what should be done? By James Love

Pt 5. Double billed: Why we’re paying high prices for drugs — and why we shouldn’t need to By Manica Balasegaram

Pt 6. In drug development, openness can compete with secrecy, given the chance By Mat Todd

[…] post Talking about Drug Prices & Access to Medicines: Els Torreele, Open Society Foundations appeared first on Your […]

[…] The PLOS Medicine Blog launched a series on Drug Prices and Access to medicines and calls for guest posts: blogs@plos.org. In the series’ first article, Els Torreele, Access to Medicines Director in the Public Health Program of Open Society Foundations, claims that “Only a radical overhaul can reclaim medicines for the public interest” […]

[…] Only a radical overhaul can reclaim medicines for the public interest By Els Torreele […]

[…] For those of us working to improve pharmaceutical pricing policy and make medicines affordable for all, the Senate Finance Committee’s findings on hepatitis C come as no surprise. We have seen the same kind of price gouging of patients with cancer, multiple sclerosis, and other illnesses. As a leading lobbying force in Washington bound by few constraints, the pharmaceutical industry’s arbitrary price setting and extreme profiteering is the rule, not the exception. […]

[…] Para aquellos de nosotros que trabajan para mejorar la industria farmacéutica, política de precios y hacer accesible a todos los medicamentos, las conclusiones de la Comisión de finanzas del Senado sobre la hepatitis C es de extrañar. Hemos visto el mismo tipo de manipulación de precios de los medicamentos requieren pacientes con cáncer, esclerosis múltiple y otras enfermedades. A través de una fuerza de cabildeo de los líderes en Washington marcada por algunas limitaciones, la industria farmacéutica tiene la arbitraria fijación de precios y la especulación extrema como l… […]

[…] six-part series “Talking About Drug Prices…” is a collaboration between PLOS BLOGS and PLOS Medicine with prominent global health leaders and […]

[…] a full 70 percent of the medicine brought to market by the industry in the past 20 years provided no therapeutic benefit over the products already available. Instead, these “me too” drugs were put forward in order […]

[…] a full 70 percent of the medicine brought to market by the industry in the past 20 years provided no therapeutic benefit over the products already available. Instead, these “me too” drugs were put forward in order […]

[…] a full 70 percent of the medicine brought to market by the industry in the past 20 years provided no therapeutic benefit over the products already available. Instead, these “me too” drugs were put forward in order to […]

[…] a full 70 percent of the medicine brought to market by the industry in the past 20 years provided no therapeutic benefit over the products already available. Instead, these “me too” drugs were put forward in order […]

[…] a full 70 percent of the medicine brought to market by the industry in the past 20 years provided no therapeutic benefit over the products already available. Instead, these “me too” drugs were put forward in order […]

[…] medicamento, lo más probable es que no ofrezca ningún valor a la sociedad. Sorprendentemente, un 70% de los medicamentos puestos en el mercado por la industria en los últimos 20 años no ha aportado ningún beneficio […]

[…] medicamento, lo más probable es que no ofrezca ningún valor a la sociedad. Sorprendentemente, un 70% de los medicamentos puestos en el mercado por la industria en los últimos 20 años no ha aportado ningún beneficio […]

[…] medicamento, lo más probable es que no ofrezca ningún valor a la sociedad. Sorprendentemente, un 70% de los medicamentos puestos en el mercado por la industria en los últimos 20 años no ha aportado ningún beneficio […]

[…] medicamento, lo más probable es que no ofrezca ningún valor a la sociedad. Sorprendentemente, un 70% de los medicamentos puestos en el mercado por la industria en los últimos 20 años no ha aportado ningún beneficio […]

[…] often targets less critical health needs (think erectile dysfunction or cosmetic drugs) or is a “me too” drug, a non-innovative medicine aimed at carving out a piece of an existing lucrative market. So the NIH […]

[…] often targets less critical health needs (think erectile dysfunction or cosmetic drugs) or is a “me too” drug, a non-innovative medicine aimed at carving out a piece of an existing lucrative market. So the NIH […]

[…] Drug Prices & Access to Medicines Pt 1: By Els Torreele, Open Society Foundations. PLoS Blog, https://blogs.plos.org/yoursay/2015/10/13/talking-about-drug-prices-access-to-medicines/ Consultado el 28 de noviembre de […]

[…] That ratio reflects the industry’s need to pitch new products that are predominately “me too” drugs, so named because they offer no new therapeutic benefit. Instead, they are aimed at carving out a […]